Tariffs and Retaliation: a Macroeconomic Analysis

Implementation of the “Liberation Day” tariffs on the US’ trading partners would have far-reaching consequences for international trade patterns and the US and global economies. This column models the effects of an unanticipated permanent unilateral tariff imposed by the US and an assumed equal reaction on the part of the rest of the world. The findings suggest that tariffs of the size being currently proposed and the assumed retaliation may have significant short-run and long-run costs on output levels, inflation rates, and welfare. They also emphasise the importance of sticky prices and the monetary policy response to the tariff shock in shaping the short-run responses to the tariff shock and the global retaliation.

This article co-authored by Stéphane Auray, Professor of Econonomics at ENSAI, researcher at CREST, Michael B. Devereux, Professor of Economics at the Vancouver School of Economics University Of British Columbia and Aurélien Eyquem, Associate Professor of Economics HEC Lausanne, was originally published on VoxEU, CEPR‘s policy portal on May 27, 2025.

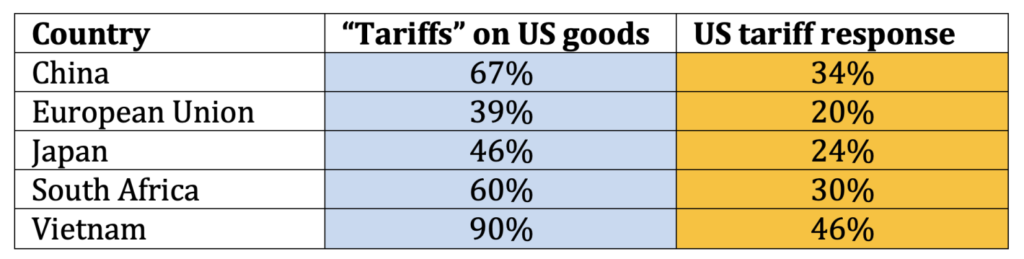

The US introduction of wide-ranging “Liberation Day” tariffs on all its trading partners is set to have far-reaching consequences for international trade patterns and the US and global economies. These measures, although not yet fully implemented, consist of a universal baseline tariff of 10%, alongside higher rates targeting countries with substantial bilateral trade surpluses with the US. If the tariffs are fully implemented and remain in effect, they are expected to profoundly reshape existing trade relationships and economic structures. Table 1 documents the proposed “Liberation Day” tariff schedule for a number of countries.

Table 1 Liberation Day tariff schedule

For a large country such as the US, a tariff can raise welfare by improving the terms of trade, since the US market power in world markets can lead its trading partners to accept lower prices in return for exporting to the US. But the tariff also represents a large macroeconomic shock, restricting supply chains for intermediate imports and, to the extent that foreign exporters do not bear all the burden of adjustment, raising domestic consumer prices in the US.

It is highly unlikely, however, that the rest of the world will passively accept large unilateral tariffs on their exports to the US. They will surely respond with retaliatory tariffs of their own. In this case, the terms of trade benefits for the US would fall, and overall global trade volume will shrink. By the same token, the macroeconomic effects of a global trade war would be highly contractionary.

In a recent paper (Auray et al. 2025b), we conduct an analysis of the effects of the “Liberation Day” tariffs in a two-country New Keynesian model calibrated to represent the US and the rest of the world (ROW). We simulate the short-run and long-run effects of an unanticipated permanent unilateral tariff imposed by the US and an assumed equal reaction on the part of the rest of the world. Our view is that the tariff shock and retaliation will have two distinct impacts on the trading system and the world economy. The long-run impacts will be determined by the reduction in international trade, the shrinking of global supply chains, and the permanent distortionary effects on domestic consumption and factor supply. The short-run impacts will involve the aggregate demand effects, the cost-push shocks on aggregate supply, and the endogenous response of monetary policy to the inflationary effects of tariffs. Our simulation of the impact of a permanent tariff shock and retaliation is able to capture both short-run and long-run effects.

Our model allows a simple yet comprehensive evaluation of the effects of the US tariff shock and possible retaliation, incorporating the channels discussed above. We consider an arbitrary 10 percentage point increase in tariffs, without and with rest of the world retaliation. Three key features of the baseline model are important in the understanding of the response to the tariff shocks. First, the calibrated model implies a substantial asymmetry between the US and the rest of the world. While the US is the largest single economy in the world, it is small as a fraction of global GDP, and evaluated in a bilateral sense, it is more open to trade with the rest of the world than the rest of the world with the US. This implies that an equal-sized tariff in both regions leads to a larger negative output effect on the US than on the rest of the world. Second, the response to a permanent tariff is much larger in the short run than in the long run. This is due to an endogenous response of monetary policy to the burst of CPI inflation following the tariff shock. Finally, the presence of global supply chains in the form of imported intermediate goods is critical for the scale effect of the tariff response. Both the impact and long run negative effects of the tariff shock would be substantially smaller in the absence of imported intermediate goods.

Our paper represents one contribution to a large recent commentary on the sweeping new trade tariffs announced and imposed by the new US administration (see Attinasi and Mancini 2025, Baldwin and Barba Navaretti 2025, Conteduca et al. 2025, Evenett, and Fritz 2025 and Fajgelbaum et al. 2024, among many others).

The modelling approach

We describe a model with a ‘Home’ and ‘Foreign’ country, supposed to represent the rest of the world and the US, respectively. Firms use labour and traded intermediate goods to produce, and prices are sticky following the Rotemberg specification. The full description of the model is in Auray et al. (2024 and 2025a.)

Our approach is to quantify the effects of a large, unanticipated, and permanent increase in the Foreign tariff on imported goods on GDP, consumption, CPI inflation, the terms of trade, the trade balance, and welfare in both countries. We add to this by assuming a one for one retaliation by the Home country. We match the size of the US economy, tariffs, or elasticities to either real world data or what is accepted in the literature (e.g. Bergin and Corsetti 2023, Feenstra et al. 2018).

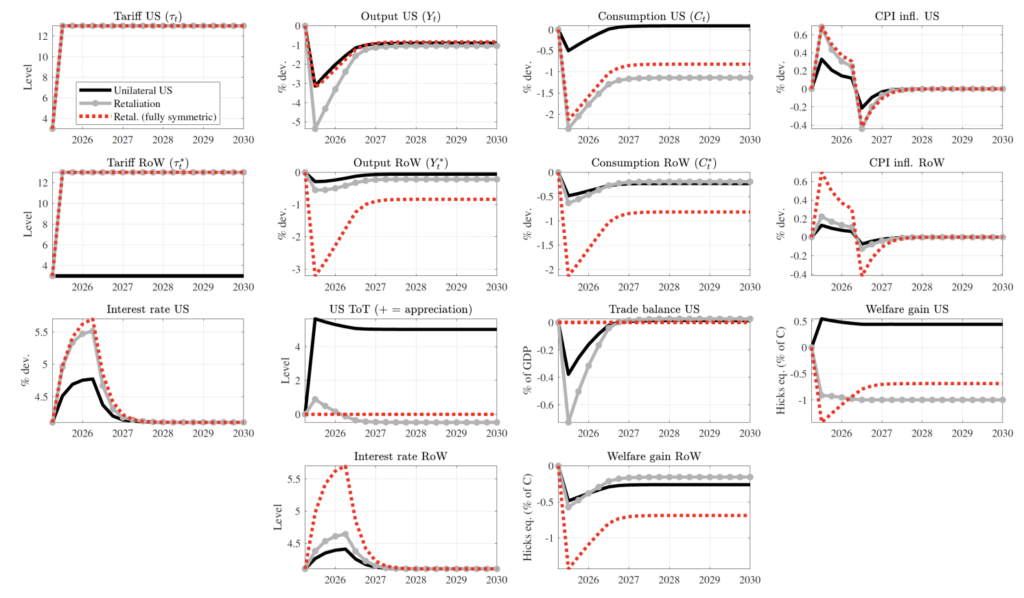

Figure 1 shows our baseline results. A 10% increase in US tariffs reduces US output by nearly 3% on impact, reducing US consumption by 0.5%. It raises US CPI inflation by 0.3%, leading to a rise in the US policy rate by more than 60 basis points. The US terms of trade appreciate, but the price of intermediate imports rises. This is a key driver of the decline in US output. The large fall in output with a muted effect on consumption leads the US trade balance to significantly deteriorate on impact.

Figure 1 Impulse responses to a 10 percentage point tariff shock

Note: RoW: Rest of the world.

Although US output and consumption fall, in welfare terms US households experience a gain of approximately 0.5% in consumption equivalent terms on impact (0.4% in the long run), primarily driven by the reduction in their labour supply. In contrast, households in the rest of the world face an equivalent welfare loss on impact – around 0.5% of consumption equivalent – although this loss gradually converges to its long-run value of 0.26% after a few quarters. The figure also shows that following the US tariff increase, output in the rest of the world declines only slightly. The rest of the world’s exposure to trade with the US is much smaller than that of US households to trade with the rest of the world.

While these results are instructive, the unilateral case is not the most plausible scenario. Assuming that the rest of world enacts a one-for-one retaliatory tariff, the negative effects on US output and consumption and the increase in inflation are much larger. Although the US tariff is fully matched by that in the rest of the world, the terms of trade still move in favour of the US, due to the asymmetry in openness between the US and all other countries. But now US consumers experience a welfare loss greater than the loss suffered by the rest of the world.

Why does the symmetric tariff increase affect the US economy so much more severely than the rest of the world? Because the US is substantially more reliant on trade with the rest of the world than the reverse, it is disproportionately affected. This underscores the importance of a coordinated response of the rest of the world to US tariffs. While the US is the largest single economy in the world and is the largest export market for many countries, it is still a small share of the world economy and world trade. This point is illustrated by an alternative calibration in Figure 1, which makes the counterfactual assumption of a tariff with full retaliation, except assuming two equal-sized countries. In this case, the fall in US output is much less than in our baseline case with retaliation, and of course, the trade balance and the terms of trade are unaffected.

Alternative assumptions on supply chains and price setting

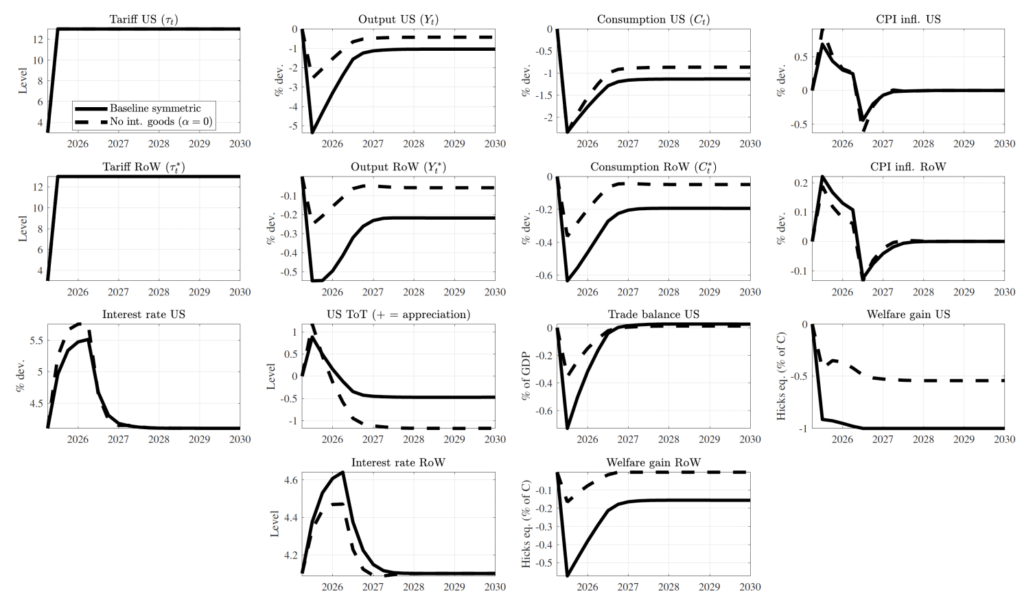

To illustrate the importance of the various mechanisms in our model we look at two alternative calibrations of the model. Figure 2 shows the response to the trade war in the absence of intermediate goods in production, assuming output is produced only by labour. While the qualitative response of output, the terms of trade, and the trade balance is similar to the baseline case, the scale is substantially different. Output in both countries falls much less than in the baseline case. This underscores the importance of intermediate imports in production and the role of supply chains in magnifying the effect of the tariff shock.

Figure 2 Ten percentage point symmetric tariff hike: Baseline versus no intermediate goods in production

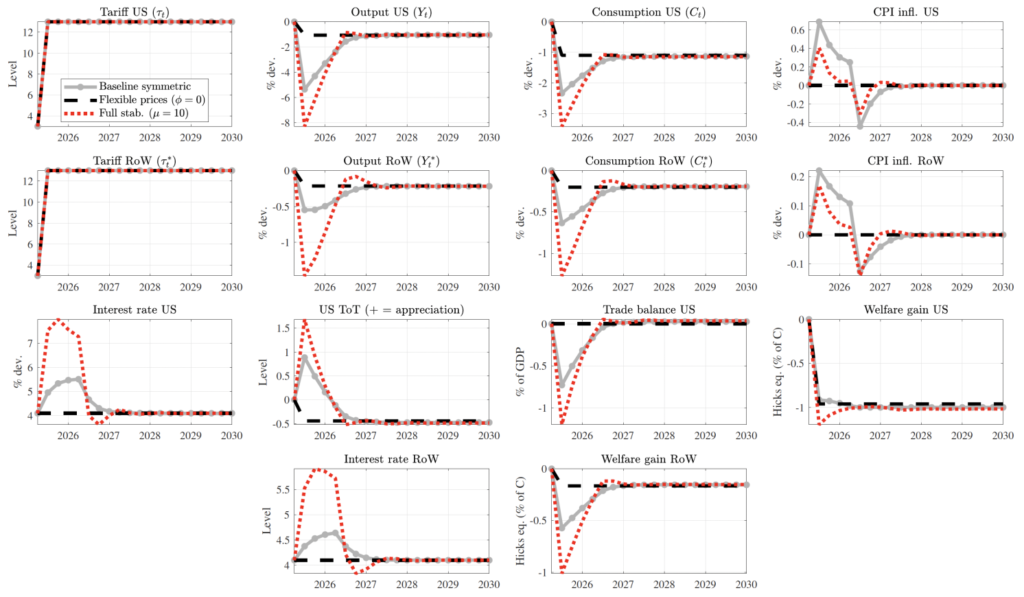

The second variant we look at is the importance of the monetary policy response. To highlight this mechanism, Figure 3 assumes fully flexible prices, so that monetary policy plays no role at all in the adjustment process. In both countries, output and consumption decline much more gradually before converging to their negative long-run value. The US terms of trade actually deteriorate, coming from the fall in US consumption, with home bias in spending patterns, and the trade balance is essentially unaffected. While the long-run dynamics are identical to the baseline model, the negative impact effects of the tariff shocks are much larger when firms cannot adjust prices instantaneously. This demonstrates one of the major contributions of our analysis, namely, emphasising the importance of sticky prices and the monetary policy response to the tariff shock in shaping the short-run responses to the tariff shock and the global retaliation.

Figure 3 Ten percentage point symmetric tariff hike: Baseline versus alternative monetary policies

Note: RoW: Rest of the world.

Finally, we study the effects of tariff hikes for the US and the rest of the world in the different cases explored after one year and after five years. Overall, the short-run results find large negative effects on US output ranging from -0.5% to more than -7%. Inflationary effects range from zero (flexible prices or full stabilisation monetary policy) to more than 0.6 percentage points. The tariff hike generates welfare gains for US consumers only in the unilateral case; all other cases bring moderate to large welfare losses. Similarly, in almost all cases the tariff hike generates trade deficits in the US. The effects in the rest of the world are much more moderate although not negligible. After five years, economies have almost converged to their new long-run values implied by tariffs. Qualitatively speaking the direction of changes is very similar looking at output and consumption, but somewhat smaller given that short-run dynamics and amplification induced by monetary policy vanished. US output still falls substantially – between -0.8% and -3.3% depending on cases. US consumption is also quite lower than before the tariff hikes – except in the case of a unilateral tariff setting – and US consumers experience moderate to large welfare losses.

Our results suggest that tariffs of the size being currently imposed and the suggested retaliation may have significant short-run and long-run costs on output levels, inflation rates, and welfare.

References

Attinasi, M G and M Mancini (2025), “Trade wars and fragmentation: Insights from a new ESCB report”, VoxEU.org, 28 March.

Auray, S, M B Devereux, and A Eyquem (2024), “Trade Wars, Nominal Rigidities and Monetary Policy”, accepted for Review of Economic Studies.

Auray, S, M B Devereux, and A Eyquem (2025a), “Trade wars and the optimal design of monetary rules”, Journal of Monetary Economics 151.

Auray, S, M B Devereux, and A Eyquem (2025b), “Tariffs and Retaliation: A Brief Macroeconomic Analysis,” NBER Working Paper 33739.

Baldwin, R and G Barba Navaretti (2025), “US misuse of tariff reciprocity and what the world should do about it”, VoxEU.org, 10 April.

Bergin, P R and G Corsetti (2023), “The Macroeconomic Stabilization of Tariff Shocks: What is the Optimal Monetary Response?”, Journal of International Economics 143: 103758.

Conteduca, F P, M Mancini, G Romanini, A E Borin, S Giglioli, M G Attinasi, L Boeckelmann, and B Meunier (2025), “Fragmentation and the future of GVCs”, Bank of Italy Occasional Papers.

Conteduca, F P, M Mancini, and A E Borin (2025), “Roaring tariffs: The global impact of the 2025 US trade war”, VoxEU.org, 6 May.

Evenett, S and J Fritz (2025), “US reciprocal tariffs: Upending the global trade policy landscape”, VoxEU.org, 3 April.

Fajgelbaum, P, P Goldberg, P Kennedy, A Khandelwal and D Taglioni (2024), “The US-China trade war and global reallocations”, American Economic Review: Insights 6(2): 295-312.

Feenstra, R C, P Luck, M Obstfeld, and K N Russ (2018), “In Search of the Armington Elasticity”, Review of Economics and Statistics 100.

Find out more about Stéphane Auray and research at ENSAI.